The way Margaret Plattner sees it, veterans are a good investment for employers.

"They've had leadership training, discipline training, they know how to be at work on time, they know how to be responsible," said Plattner, deputy commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Veterans Affairs.

But sometimes, veterans entering the civilian workforce have to overcome stereotypes that they might be unreliable, or even violent, due to combat-related stress or mental illness.

And that's generally unfair and unfounded, experts say.

"There clearly are some employers who get nervous about veterans because they've seen the media and kind of the sensationalized cases, and they think it's probably going to happen to them," said Tony Zipple, president and chief executive of Seven Counties Services in Louisville.

But even veterans with a mental illness "aren't likely to explode in the way you see on TVs and (in the) movies," said Eric Russ, a licensed clinical psychologist at the University of Louisville. "That kind of behavior is very rare."

Just as with civilian hires, he said, "You might not even know that someone you're working with or someone you know is suffering."

Still, mental health issues, along with blast wounds, have been called the "signature injuries" of the military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Last year, a report from the Institute of Medicine noted that an estimated 13 percent to 20 percent of the 2.6 million U.S. service members who'd served in Iraq or Afghanistan since 2001 may have post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition marked by flashbacks, avoidance and being easily startled.

And earlier this year, USA TODAY reported that mental-health problems, such as PTSD, led to more hospitalizations than any other medical condition in the military in 2012. In some cases, troops remained hospitalized more than a month.

Zipple said that while veterans are more likely to suffer from PTSD, depression, substance abuse and anxiety-related condition! s than the general population, that doesn't "necessarily make them any worse or any riskier of a hire."

"A very, very large cross-section of the general population has some combination of these same conditions as well," Zipple said. "If you said we're not going to hire anybody that has an issue with depression and takes an antidepressant, you'd have big chunks of the population that would never work again."

Millions have PTSD

About 7.7 million U.S. adults — or about 3.5 percent of the American adult population — have post-traumatic stress disorder, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Mood disorders, including chronic depression and bipolar disorder, affect about 20.9 million U.S. adults, or about 9.5 percent of the U.S. adult population.

Anyone can develop PTSD after a traumatic event, such as a car accident or a natural disaster, said Tom Lawson, an Army veteran and professor in UofL's Kent School of Social Work. "That doesn't mean that you're still not a good employee or cannot work."

Former Marine Rebecca Munoz, photographed Monday, Nov. 4, 2013, stands outside of the VA Hospital where she is currently a peer support specialist.(Photo: Alton Strupp, The (Louisville, Ky.) Courier-Journal)

Rebecca Muñoz, a Marine Corps veteran who has dealt with mental illness, puts it this way: "I am Rebecca who happens to have a diagnosis and that's all it is. It's like having diabetes, high blood pressure — no different. That's all it is."

Furthermore, "most veterans come back without any diagnosable mental illness," said Russ, an assistant professor in the UofL Department of Psychiatry. For those veterans who need help with PTSD, depression and substance abuse, "we have a much better understanding of a! ll of the! se conditions than we did say, for example, in Vietnam," Russ said.

And "the outlook is really good if they get treatment," he said. "The longer you go with an untreated illness, the more likely it is to interfere with your life," leading to job loss or other problems, such as troubled relationships with friends and spouses.

Muñoz, 41, of Louisville received treatment from the Veterans Affairs Medical Center to cope with bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness. The condition, which causes shifts in mood and energy, had led other treatment providers to tell her to stop trying to find work and file for disability instead.

But with help from the VA Medical Center's Compensated Work Therapy program, she was able to control her illness and now works as a peer support specialist for the VA, helping other veterans recover from mental illness.

Through her work with the VA, Muñoz said she's found that employers often are willing to make adjustments to help a good employee. For example, they may let PTSD sufferers who don't like loud noises wear headphones. "There are ways to advocate for yourself and there are places who can help you advocate for yourself," she said.

Army veteran John Penezic, 46, of Louisville said some veterans choose to cope with their symptoms by isolating themselves in some way. For example, he avoided fireworks shows for years because the "booms" would eat at him and crowds made him uncomfortable. Also, after ending his 16-year military career in 2008, he would gravitate toward jobs that would allow him to work around other veterans such as doing outreach with homeless veterans for the Volunteers of America of Kentucky.

"Many veterans feel that 'Civilians won't understand me,'" said Penezic, who's dealt with PTSD symptoms for years but never been formally diagnosed.

Finding a good match

When looking to hire a veteran — or anyone else — it's important to look at various factors to determine whether the person is a good m! atch, Zip! ple said. "If they've got the qualifications and they've got good work experience and they've got good references, I wouldn't think of them as being any riskier (of a) hire than anyone else in the general population," he said.

Furthermore, "if they're getting decent supports and services, if they're getting good treatment, there's no reason why they can't be hugely successful in every walk of life," he said.

Netflix on your cable box? It may happen

Netflix on your cable box? It may happen

) reported lower first quarter profits as its production costs increased.

) reported lower first quarter profits as its production costs increased.

Inside Apple's new iOS 7

Inside Apple's new iOS 7  iPhones 5C and 5S good enough for Apple

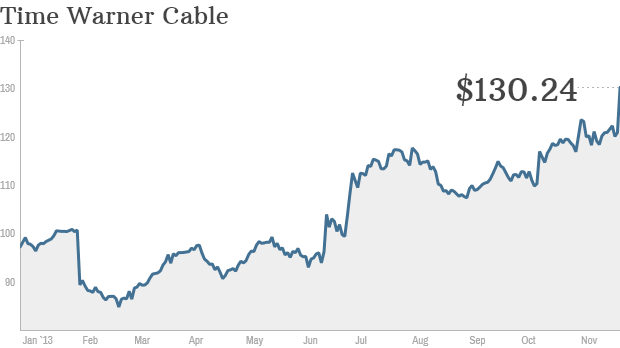

iPhones 5C and 5S good enough for Apple  Being more than 200 years old, the stock market has had time to foster a staggering number of axioms, tips, disciplines and lessons. Indeed, one thing there’s never a shortage of on Wall Street is advice.

Being more than 200 years old, the stock market has had time to foster a staggering number of axioms, tips, disciplines and lessons. Indeed, one thing there’s never a shortage of on Wall Street is advice. This might have been solid advice a couple of decades ago when a stock’s price was a reflection of a company’s operation, slightly adjusted higher or lower depending on the organization’s plausible outlook.

This might have been solid advice a couple of decades ago when a stock’s price was a reflection of a company’s operation, slightly adjusted higher or lower depending on the organization’s plausible outlook. The market may be tricky, inconsistent, exhausting, unduly-influenced, erratic and unpredictable, but it’s not rigged.

The market may be tricky, inconsistent, exhausting, unduly-influenced, erratic and unpredictable, but it’s not rigged. Aside from sticking with safe and stable names simply as a way to maintain your sanity, the industry often encourages a focus on value stocks by noting they actually yield better bottom results over the long haul. Problem: It’s only true sometimes. Other times, it’s completely untrue.

Aside from sticking with safe and stable names simply as a way to maintain your sanity, the industry often encourages a focus on value stocks by noting they actually yield better bottom results over the long haul. Problem: It’s only true sometimes. Other times, it’s completely untrue. Odds are that you’ll never successfully step into a stock right in front of an acquisition for any reason other than luck. Suitors make a point of keeping the lid on M&A plans specifically to avoid front-running a buyout and driving up a price. And, in the rare case where news of an impending buyout is leaked, there’s always someone with closer ties that can act on the information sooner than you can (assuming you’re not in those particular board meetings).

Odds are that you’ll never successfully step into a stock right in front of an acquisition for any reason other than luck. Suitors make a point of keeping the lid on M&A plans specifically to avoid front-running a buyout and driving up a price. And, in the rare case where news of an impending buyout is leaked, there’s always someone with closer ties that can act on the information sooner than you can (assuming you’re not in those particular board meetings). There’s actually a little bit of truth to this axiom that Jim Cramer turned into an outright cliche. There’s an important footnote missing from the idea, however.

There’s actually a little bit of truth to this axiom that Jim Cramer turned into an outright cliche. There’s an important footnote missing from the idea, however.